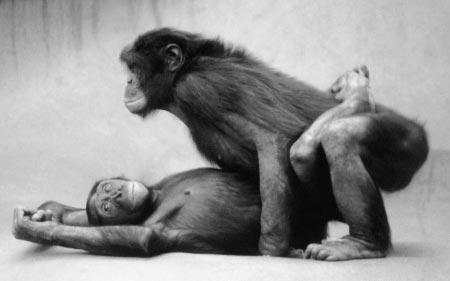

Male bonobos, too, may engage in pseudocopulation but generally perform a variation. Standing back to back, one male briefly rubs his scrotum against the buttocks of another. They also practice so-called penis-fencing, in which two males hang face to face from a branch while rubbing their erect penises together.

The diversity of erotic contacts in bonobos includes sporadic oral sex, massage of another individual's genitals and intense tongue-kissing. Lest this leave the impression of a pathologically oversexed species, I must add, based on hundreds of hours of watching bonobos, that their sexual activity is rather casual and relaxed. It appears to be a completely natural part of their group life.

Based on an analysis of many such incidents, my study yielded the first solid evidence for sexual behavior as a mechanism to overcome aggression. Not that this function is absent in other animals – or in humans, for that matter – but the art of sexual reconciliation may well have reached its evolutionary peak in the bonobo.

For these animals, sexual behavior is indistinguishable from social behavior.

It has been speculated by anthropologists – including C. Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University and Helen Fisher of Rutgers University – that sex is partially separated from reproduction in our species because it serves to cement mutually profitable relationships between men and women. The human female's capacity to mate throughout her cycle and her strong sex drive allow her to exchange sex for male commitment and paternal care, thus giving rise to the nuclear family.

This arrangement is thought to be favored by natural selection because it allows women to raise more offspring than they could if they were on their own. Although bonobos clearly do not establish the exclusive heterosexual bonds characteristic of our species, their behavior does fit important elements of this model. A female bonobo shows extended receptivity and uses sex to obtain a male's favors when – usually because of youth – she is too low in social status to dominate him.

At the San Diego Zoo, I observed that if Loretta was in a sexually attractive state, she would not hesitate to approach the adult male, Vernon, if he had food. Presenting herself to Vernon, she would mate with him and make high- pitched food calls while taking over his entire bundle of branches and leaves. When Loretta had no genital swelling, she would wait until Vernon was ready to share. Primatologist Suehisa Kuroda reports similar exchanges at Wamba: "A young female approached a male, who was eating sugarcane. They copulated in short order, whereupon she took one of the two canes held by him and left."

Human family life implies paternal investment, which is unlikely to develop unless males can be reasonably certain that they are caring for their own, not someone else's, offspring. Bonobo society lacks any such guarantee, but humans protect the integrity of their family units through all kinds of moral restrictions and taboos.

Thus, although our species is characterized by an extraordinary interest in sex, there are no societies in which people engage in it at the drop of a hat (or a cardboard box, as the case may be). A sense of shame and a desire for domestic privacy are typical human concepts related to the evolution and cultural bolstering of the family.

Source